The EWNS can disinfect air but start off as nothing more than atmospheric water vapour

The EWNS can disinfect air but start off as nothing more than atmospheric water vapour

Despite advances in antibiotics, vaccines and infection control, infectious diseases continue to affect hundreds of millions of people each year and the number of antibiotic resistant bacteria is on the rise. Therefore, there is an urgent need for innovative, effective and low-cost technologies in the battle against airborne infections. Upper-room UV irradiation, air filtration, photocatalysis and biocidal gases are the current methods most commonly used for air disinfection. However, these methods come with a variety of drawbacks such as potential health risks and high costs.

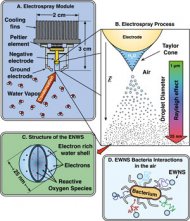

Philip Demokritou and colleagues from the Harvard School of Public Health and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health in the US, have designed a system that transforms atmospheric water vapour into EWNS. With a size of only 25nm, the nanostructures are highly mobile and remain in room air for a long time due to their high electric charge. Disinfection of the air is achieved as the nanostructures contain reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl and superoxide radicals, which interact with the outer membranes of bacteria, rendering them inactive.

Toxicological studies on mice by Demokritou’s team have shown that the EWNS have minimal toxicological effects. No respiratory tract toxicity was found at exposure levels and times higher and longer than those needed to inactivate the bacteria. Demokritou explains that the radicals are harmless to cell membranes in the lungs of test animals because ‘the organic matter in the lung lining fluid which covers the epithelial cells neutralises the reactive oxygen species, so they never reach the cells.’

‘The proposed method has the potential to transform the way we currently control infectious diseases, ’ says Demokritou, ‘if proven effective in practice, it could be used to create “shields” to protect people in their microenvironments.’